Difference between revisions of "Chapter 15 CS4"

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

Code is language. It can be thought of as a material that hides its own materiality. When you view a website, what you see is a seamless graphic interface with text, images, and links, but all online media is constructed from code. Code is a set of instructions. Open any page in a web browser and click on the View Menu > Page Source to see the code used to create that page. This code tells the browser how to render the media elements into a seamless interface. Web pages are written in Hypertext Markup Language (HTML). We write the code so that the browser, which is called a client, can display the interface we create. In this chapter, we will explore the basics of this code. | Code is language. It can be thought of as a material that hides its own materiality. When you view a website, what you see is a seamless graphic interface with text, images, and links, but all online media is constructed from code. Code is a set of instructions. Open any page in a web browser and click on the View Menu > Page Source to see the code used to create that page. This code tells the browser how to render the media elements into a seamless interface. Web pages are written in Hypertext Markup Language (HTML). We write the code so that the browser, which is called a client, can display the interface we create. In this chapter, we will explore the basics of this code. | ||

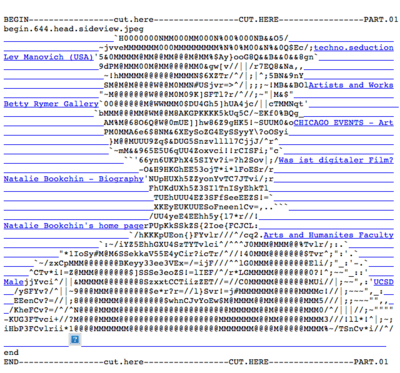

| − | While professional websites are usually programmed to hide the presence of code in a seamless graphic façade, experimental artists often revel in exposing it. The artist group Jodi (Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans) works extensively with the materiality of code. In the early moments of the dot com boom, when corporations began to stake out an aesthetic and functional claim online (95-96), Jodi hosted a series of confrontational pages. Theirs responded to the corporate attempt to professionalize the aesthetics of online media and undermine the presence of code. | + | While professional websites are usually programmed to hide the presence of code in a seamless graphic façade, experimental artists often revel in exposing it. The artist group Jodi (Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans) works extensively with the materiality of code. In the early moments of the dot com boom, when corporations began to stake out an aesthetic and functional claim online (95-96), Jodi hosted a series of confrontational pages. Theirs responded to the corporate attempt to professionalize the aesthetics of online media and undermine the presence of code. Wwwwww.jodi.org looks like random text in the browser, but viewing the source reveals a highly structured plan. A rough diagram of a nuclear bomb is made with the text of the source code. |

Jodi threw a bomb at clean design, and offered a reward to anyone aware of a web page’s material to view the source code. When code is displayed it does not account for white space. “Forgetting” this basic principle allowed Jodi to make a brilliant visual and conceptual argument for breaking the rules. | Jodi threw a bomb at clean design, and offered a reward to anyone aware of a web page’s material to view the source code. When code is displayed it does not account for white space. “Forgetting” this basic principle allowed Jodi to make a brilliant visual and conceptual argument for breaking the rules. | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

[http://www.irational.org/heath/imaging_natalie/ http://www.irational.org/heath/imaging_natalie/] | [http://www.irational.org/heath/imaging_natalie/ http://www.irational.org/heath/imaging_natalie/] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:imaging_natalie.png|400px]] | ||

= Exercise 1: Hello World! = | = Exercise 1: Hello World! = | ||

Latest revision as of 13:38, 1 February 2013

Download Materials for Chapter 15

Click here to download chapter 15 work files.

Chapter 15 - Hello World

Code is language. It can be thought of as a material that hides its own materiality. When you view a website, what you see is a seamless graphic interface with text, images, and links, but all online media is constructed from code. Code is a set of instructions. Open any page in a web browser and click on the View Menu > Page Source to see the code used to create that page. This code tells the browser how to render the media elements into a seamless interface. Web pages are written in Hypertext Markup Language (HTML). We write the code so that the browser, which is called a client, can display the interface we create. In this chapter, we will explore the basics of this code.

While professional websites are usually programmed to hide the presence of code in a seamless graphic façade, experimental artists often revel in exposing it. The artist group Jodi (Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans) works extensively with the materiality of code. In the early moments of the dot com boom, when corporations began to stake out an aesthetic and functional claim online (95-96), Jodi hosted a series of confrontational pages. Theirs responded to the corporate attempt to professionalize the aesthetics of online media and undermine the presence of code. Wwwwww.jodi.org looks like random text in the browser, but viewing the source reveals a highly structured plan. A rough diagram of a nuclear bomb is made with the text of the source code.

Jodi threw a bomb at clean design, and offered a reward to anyone aware of a web page’s material to view the source code. When code is displayed it does not account for white space. “Forgetting” this basic principle allowed Jodi to make a brilliant visual and conceptual argument for breaking the rules. In the early years of the World Wide Web bandwidth was small. A large amount of communication took place on text only list-servs, chat rooms, multi-user dungeons (MUDs), and bulletin board servers (BBS). Pages had few images on them because they took too long to download. In the absence of high-resolution images, people found creative ways of drawing with text.

Drawings made by arranging the 128 characters that are part of the American Standard Code for Information Interchange are ASCII art. Loosely defined, ASCII art is art made by text, usually in the form of figurative drawings. The shapes and densities of the characters are treated purely as formal elements to construct line, form, and shading. As an example, Heath Bunting’s 1998 portrait of Natalie Bookchin, an early net artist can be seen here

http://www.irational.org/heath/imaging_natalie/

Exercise 1: Hello World!

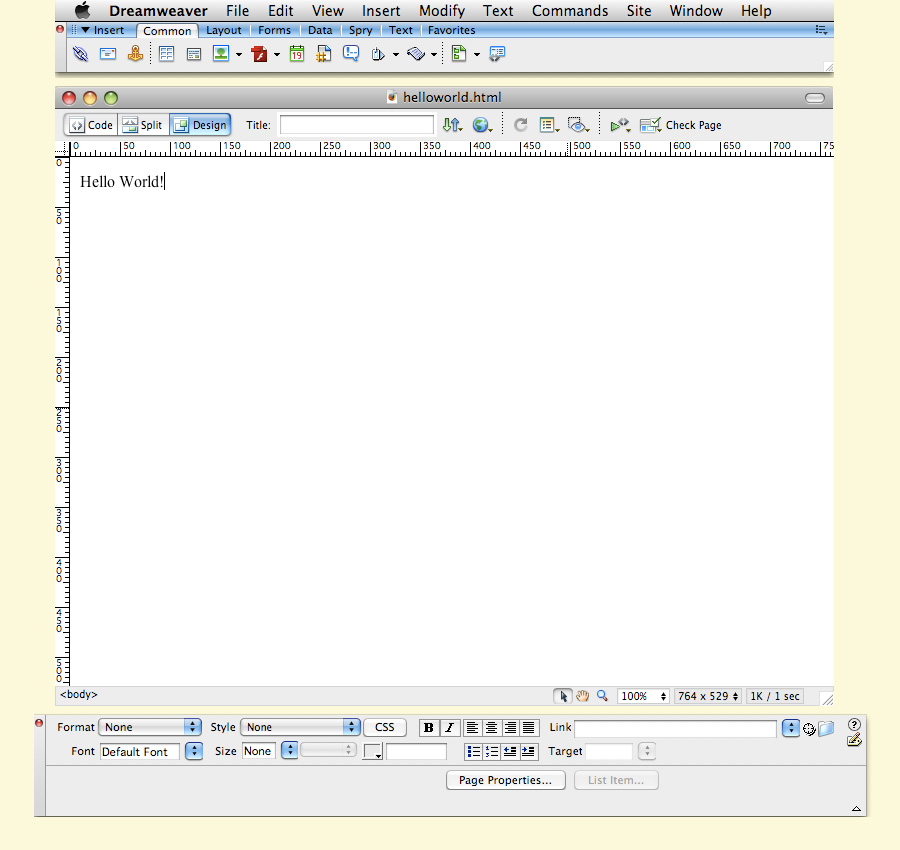

With the materiality of code in mind, we will construct our first web page. Before starting, it is important to mention that it is absolutely essential that you are aware of where your files are saved when you are working on projects that involve code. For this chapter, create a folder on your desktop or hard drive and commit to saving everything that you make from or related to this chapter into that one folder. Do not make sub-folders. Do not make more than one folder.

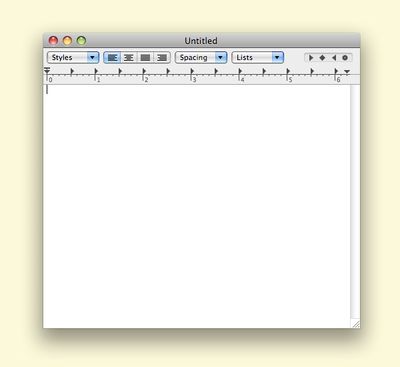

Open a text editing application, such as Text Wrangler, Text Mate, Smultron, BBEdit, or TextEdit. On a PC use Note Pad. Since we often teach this in labs with TextEdit readily available, the screen shots will be from that interface. The first and very important step in any text editing application is to make sure that it is working in Plain Text format.

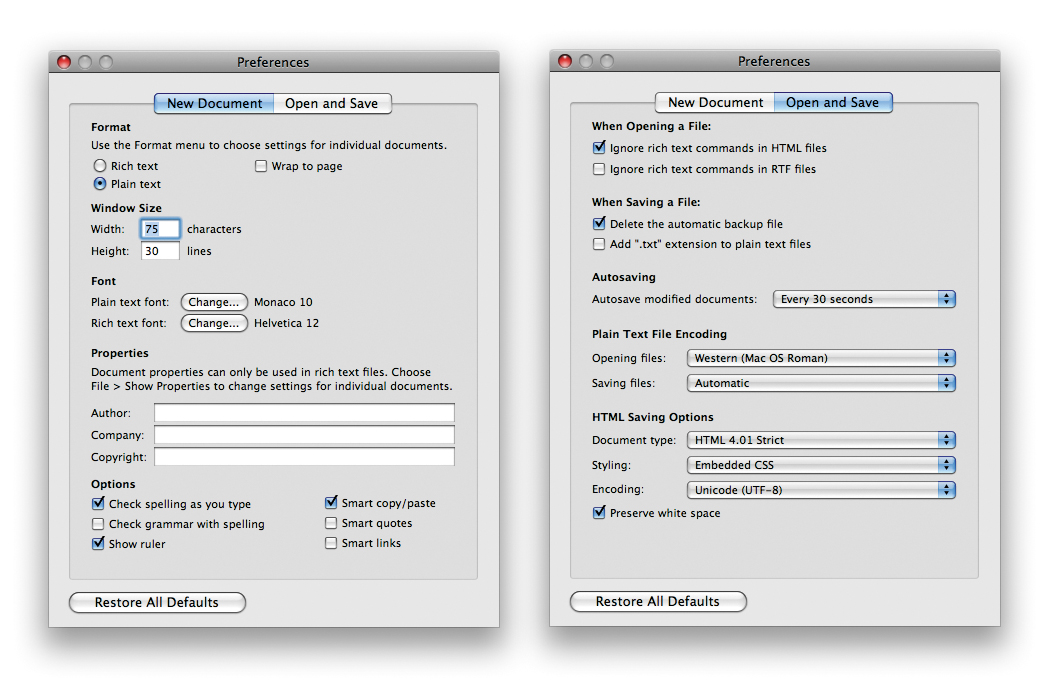

1. In Text Edit, check the preferences to make sure it is set to Plain Text. If you see rulers in the work document when you launch the application, your document is not set to Plain Text.

Click TextEdit Menu > Preferences. In the New Document dialog box, click on the "Plain text" radio button. In the Open and Save dialog box, check "Ignore rich text commands in HTML files," check "Delete the automatic backup file", and uncheck "Add '.txt' extension to plain text files." These preferences will be in effect on new documents, so close any open documents in TextEdit and click File > New to start on a new document.

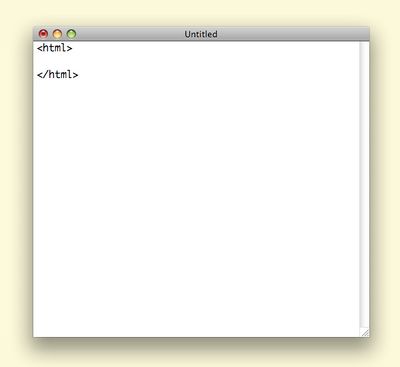

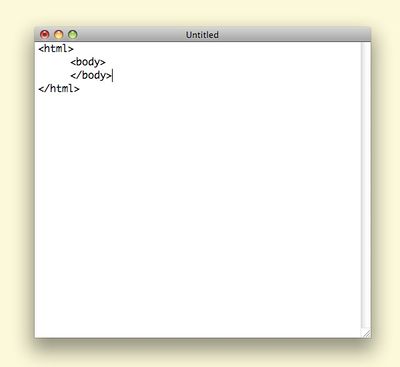

2. Type the opening and closing HTML tags as illustrated here.

Every tag opens and closes. The slash is used to close a tag. The HTML tag tells the browser that we are writing in Hyper Text Markup Language.

3. Position your cursor after the opening HTML tag. Hit Enter and press the Tab key. Tabbing is used to add visible structure to the code so that it is easier to read. Tabs do not affect the display or functionality of the code. All media placed inside the body tag is displayed on the web page. Add the opening and closing body tags.

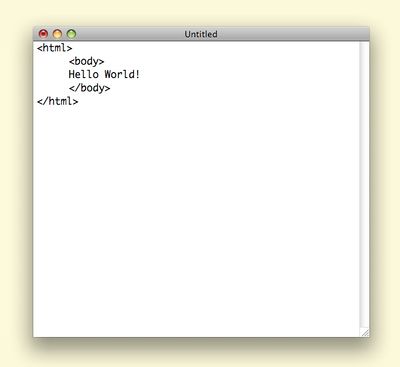

4. Inside the body tags type Hello World!

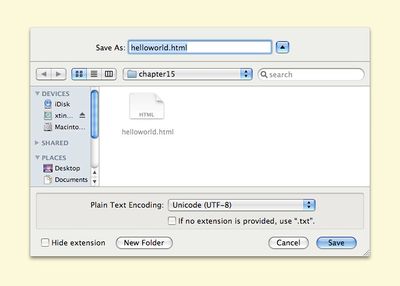

5. Save the file as helloworld.html. Make sure that you add “.html” to the end of the file name. The file extension is important. It communicates to the browser that this is an .html file.

| Watch Out: When saving files for the web, do not use capital letters, spaces, or reserved characters. (! + @ & = ?) Only use a-z, 1-9, -, and _. |

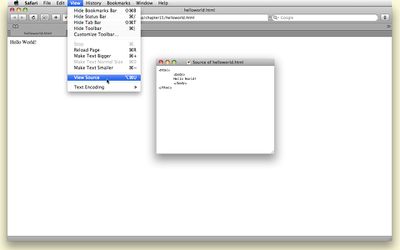

6. Open a web browser, click File > Open and find the helloworld.html file. We opened Safari, clicked File > Open File... and browsed to Desktop > Chapter 15 > helloworld.html. Notice that Hello World! is the only part of the code that is displayed. In the browser, click View > Page Source to see all of the code.

In exercise two we will be returning to this file in the web browser, so leave it open if you are going to work on that exercise next.

| Watch Out! Double-clicking on the html file in your folder may not open the file in a web browser. Be careful to open the file in a web browser if this is your intent by opening the browser and clicking File > Open File...or by dragging the html file to the browser icon in the Dock. |

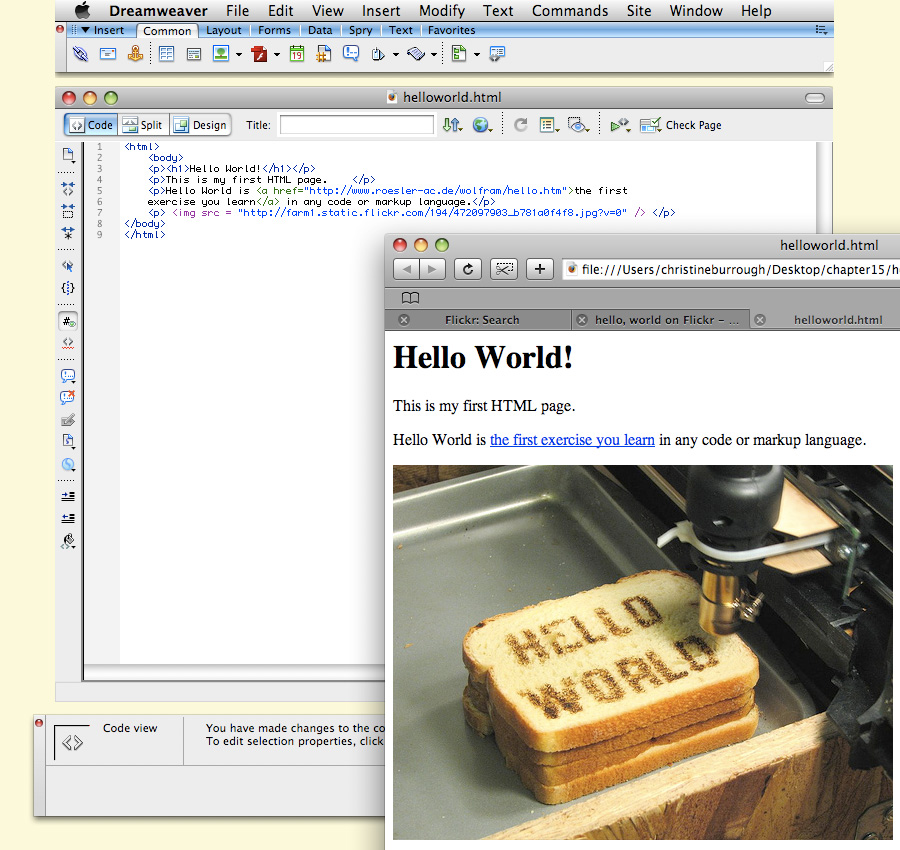

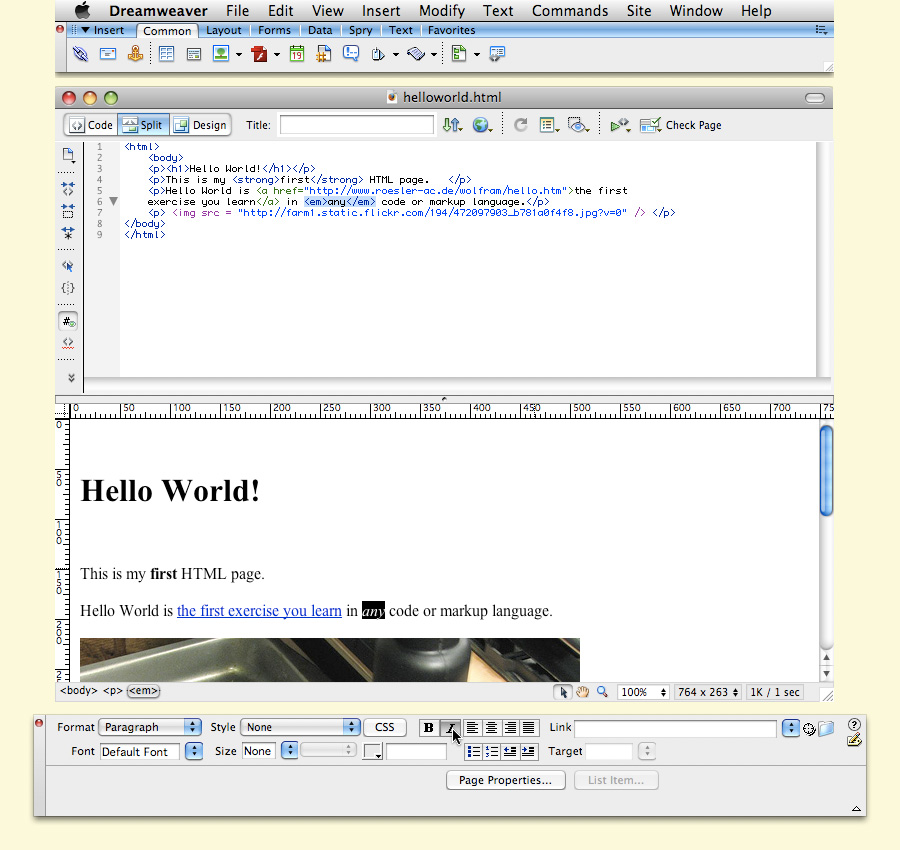

Exercise 2: Hello Dreamweaver

In the previous exercise, we wrote the Hello World! code using a text editing program. A text editor is the only application necessary for writing code. Code can be laborious when the content in the browser is more complicated than Hello World! Most artists and designers prefer to use a WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) application such as Dreamweaver to develop code. Dreamweaver actually "writes" the code for you, which makes creating the HTML file much easier.

In this exercise, we will modify the file we just made. We will "save on top of the file," meaning we will make changes to the existing file. We will not "Save As." You should have only one file in your folder at the end of this exercise.

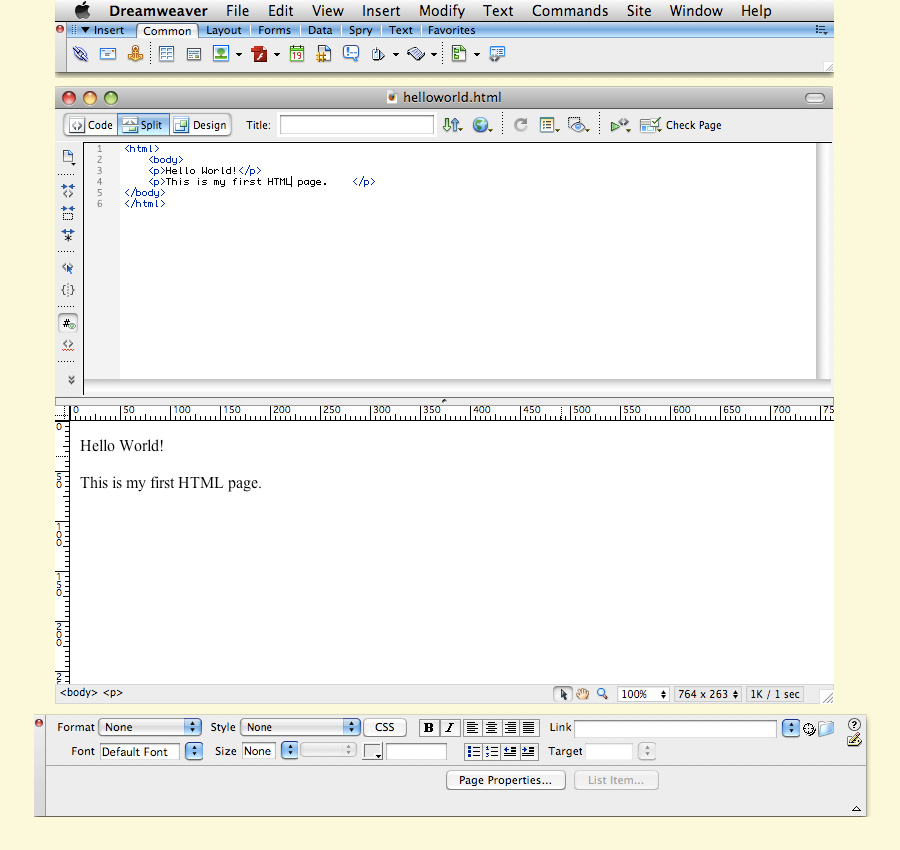

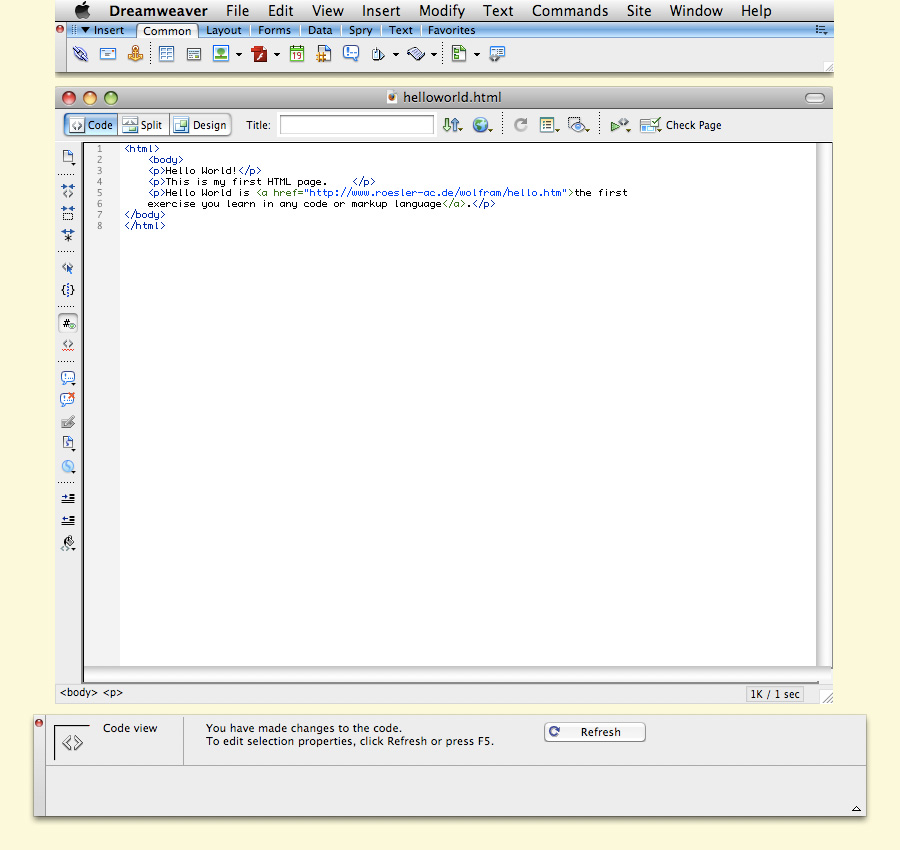

1. Open Dreamweaver from the Dock or Applications Folder. In Dreamweaver click File > Open and open the helloworld.html file. We will click File > Open then Desktop > chapter15 > helloworld.html

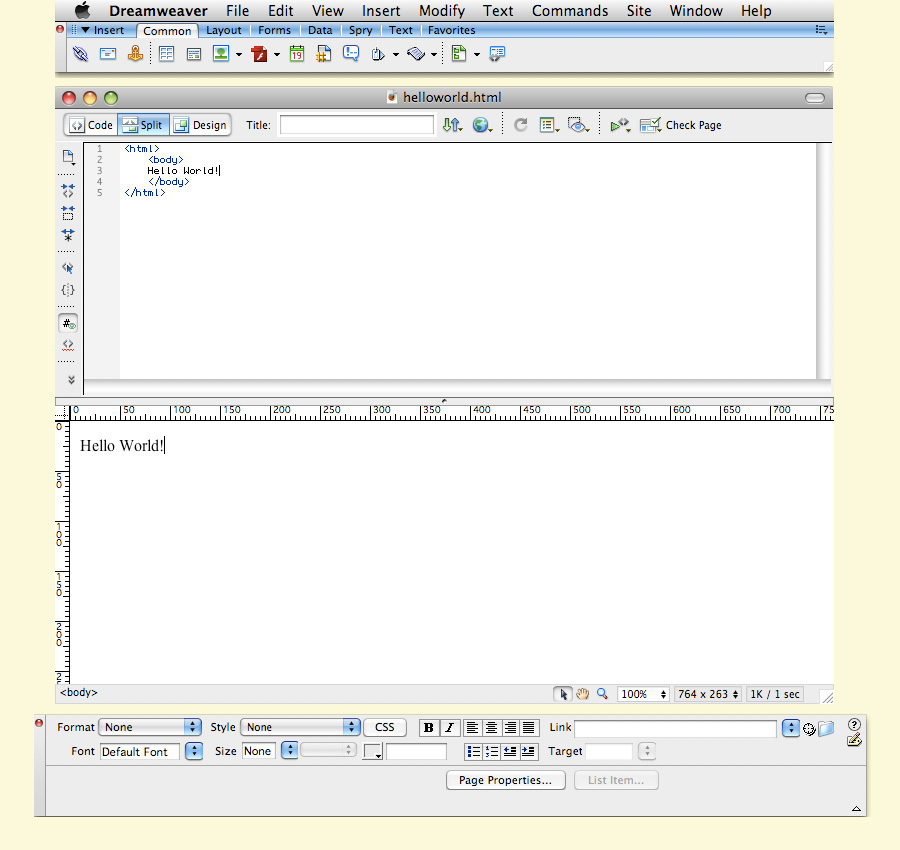

2. In the upper left corner of the document click "Split View". Split View displays both the code and the result of the code in a browser. Another way to think about this is that the code view is the instructions to the browser and the design view is the way the media looks in the browser.

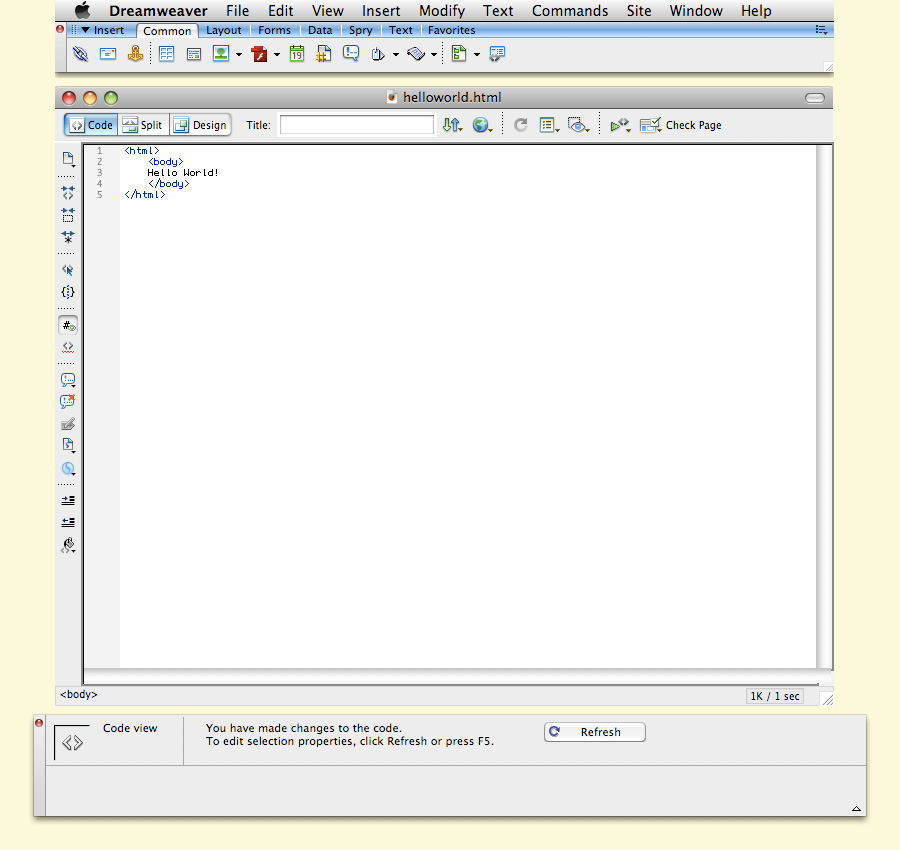

3. In the upper left corner click "Code View". Only the code is displayed. Note that your markup language is color coded. Tags are blue and text is black.

4. Click "Design View". Now we can only see the result of the code, or what will be displayed in the browser.

| Dreamweaver is a WYSIWYG editor because you can change the code by using Dreamweaver pull down menus and buttons in Design View. It should be called a WYSIWYGMOTT, or What You See Is What You Get Most Of The Time. The Design View is going to be about 95% accurate. When designing for the web, always preview your work in the browser. |

5. Switch to Split View. In the Design View half, place your cursor at the end of “Hello World!”. Hit the return key and type “This is my first HTML page”. Save the document using File > Save. Note how Dreamweaver changes the code for you. A paragraph tag has been added to the code to account for the new paragraph we made by hitting the return key in Design View.

The paragraph tag is opened and closed around the new line of text. This is an example of “nesting”. Nesting is when an open and closed tag are set inside of another open and closed tag. The relationship between where each set opens and closes is important. One is structured around the other so that they never overlap.

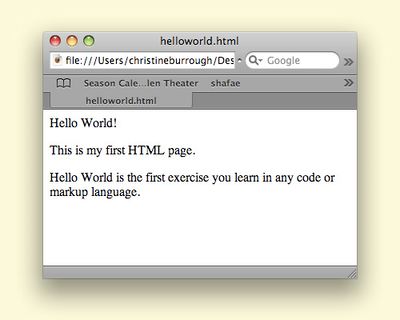

6. Return to the browser where you viewed helloworld.html in exercise one. Refresh the browser page and observe the changes we made to the file in Dreamweaver. If the file was closed, use File > Open and open the helloworld.html file. In this exercise we modified the helloworld.html file. We did not save a new file, we saved on top of the existing file. The browser displays changes to the file when changes have been made to the original file (File > Save in Dreamweaver) and the browser is refreshed (CMD+R in most browsers).

| Key Command: CMD + TAB and F9 are two MAC shortcuts for switching between applications. |

7. Go back to Dreamweaver and type a new paragraph in Design View: “Hello World is the first exercise you learn in any code or markup language.” Save the file and refresh the browser to see the new text display on the web page.

Exercise 3: Hyperlinks

Hyperlinks, or links as they are commonly called, are a one-click route from one HTML file to another. Links are the simplest form of interactivity on the web.

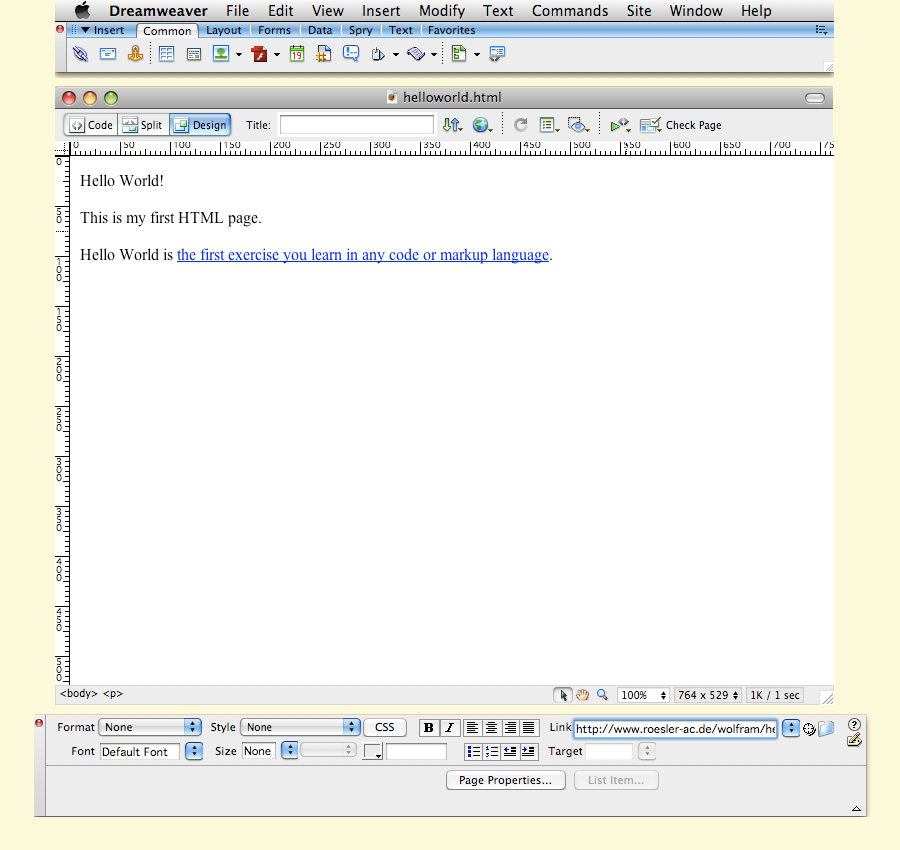

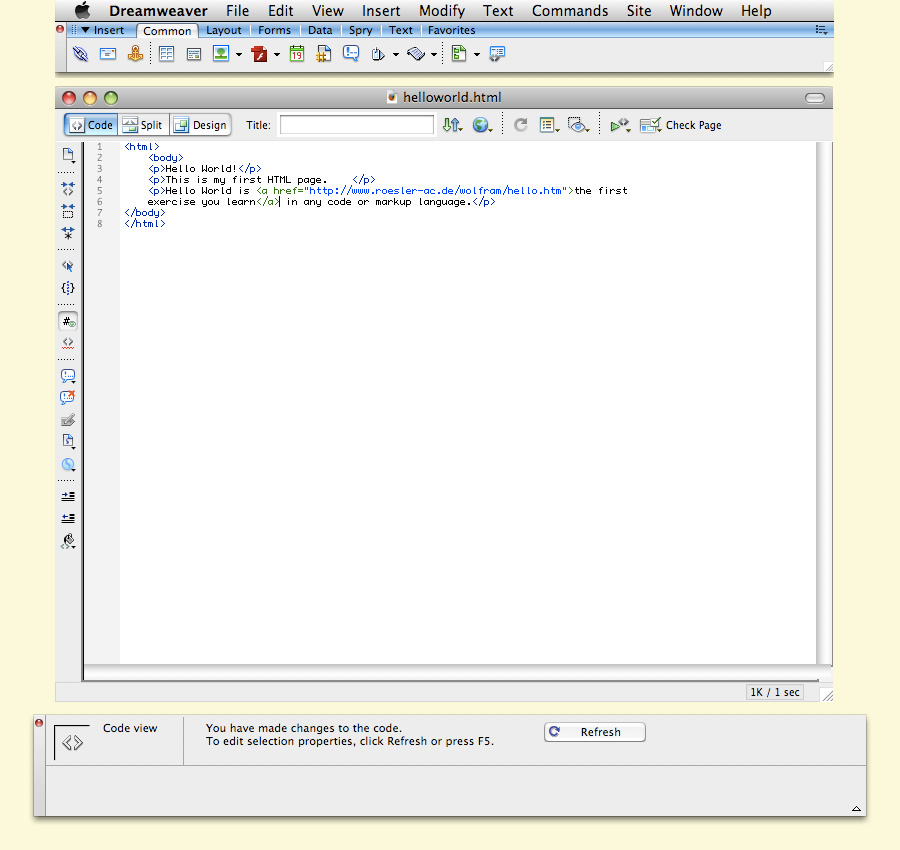

1. Open a new web browser tab or window and search for “Hello World! Collection". Click on “Hello World Collection” which is at this URL at the time of writing this book: http://www.roesler-ac.de/wolfram/hello.htm. This collection of “Hello World!” examples started in 1994, although "Hello World!" first appeared in a C programming book in 1978. Copy the link from the browser and return to the file we modified in exercise two in Dreamweaver.

In Design View, select the text “the first exercise you learn in any code or markup language” by highlighting it with your mouse. Paste the link into the field labeled “link” in the Properties Palette.

| Tip:If the Properties Palette is missing, select Window > Properties or Window > Workspace Layout > Default. |

Press the return key and it will change the selected text from body copy to a hyperlink. This is important: save the file. Remember, without saving the file, viewing the refreshed page in the browser will be disappointing.

| Watch Out!If you do not press the return key, the link will not be created. |

2. Go to the browser and refresh the helloworld.html page. The link should function in the browser. Return to Dreamweaver and inspect the code that was created.

In the code, the “a” stands for anchor. “Href” is the modifier, it tells the browser where the hypertext reference points. The value for that property is inserted after the equal sign. In this case, the value is the URL. The anchor tag is closed with slash-a, or </a>. Notice that the href tag starts just before the word, "the" and the tag closes just before the period at the end of the sentence. This part of the sentence becomes the link.

3. Move the closing anchor tag to just after the word “learn”. The link will be shortened to include only the text that is between the opening and closing tags.

Exercise 4: Images

To add an image to the HTML page, you need to have an image prepared for online viewing. Review Chapter 12 for exercises on creating a JPEG or GIF. For this exercise, we will search for an image on Flickr.com. In Chapter 2 we explained that Flickr.com is an online photo sharing website where viewers can search for images by tags. In this exercise we will use an image that has been place in the public domain with a creative commons license.

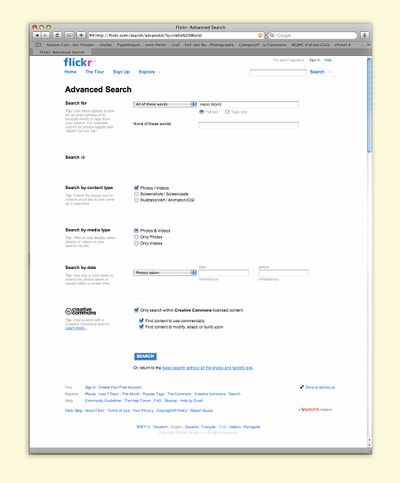

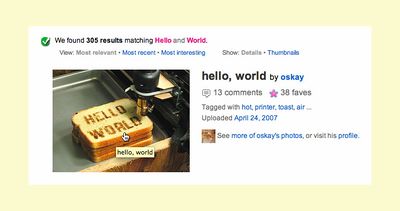

1. Go to Flickr.com. If you are not signed in, the search field is vertically centered on the right half of the page. If you are signed in, use the search field in the top left corner. Search for "Hello World."

2. On the results page, click on “Advanced Search”.

Note: The directions and screen shots for the Flickr.com interface is accurate at the time of writing this book. Web interface design changes often. It is likely that by the time you are reading this these specific directions will be out of date.

3. Scroll down and check the boxes next to “only show creative commons licensed photos”. Creative Commons is an alternative licensing schema to the standard US copyright laws. All photographs uploaded to flickr.com are automatically copyrighted, preventing other people from using or building upon them. Creative commons allows you to post your work online and license it openly, allowing others to use it in their work. Online culture is a culture of sharing, remixing, and collaboration. Creative Commons licensing enables and empowers this culture.

4. Click on an image that you found within the Creative Commons "Hello World" search. Now the image appears on the page maintained by its author (as opposed to a general results page).

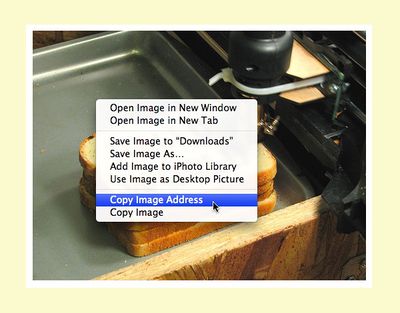

5. CTRL+Click on the image and select "Copy Image Address" (in Safari, in Firefox the language is "Copy Image Location"). This copies the URL. The URL is the path to the location where the image file is saved on the server. The next time you use Edit > Paste in any text field this address will be pasted. We will use this in Dreamweaver in the next step.

| Tip:URL stands for Universal Resource Locator. This is the web address. All web addresses that begin with "http://" point to files that are saved on servers. |

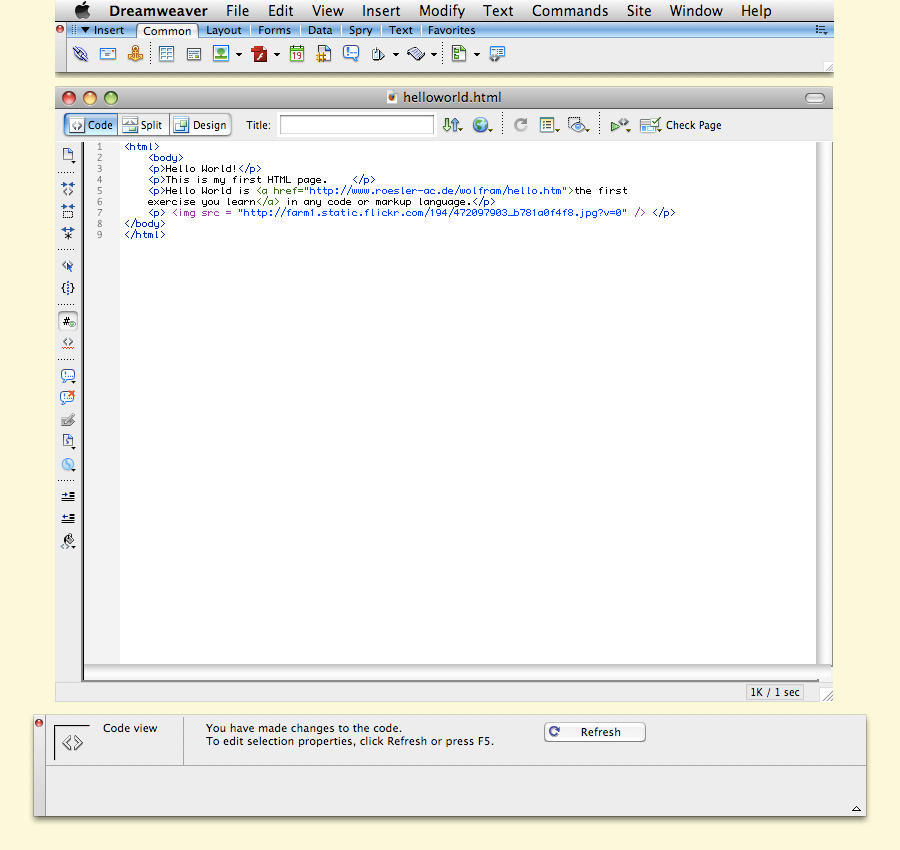

6. Go back to Dreamweaver and view the helloworld.html file in Code View. Type a new paragraph tag. Note that Dreamweaver automatically closes the tag. Now add an image tag like this, <img src=“url”/>. Replace "url" with the URL that you copied from flickr.com by pasting it into that area.

The image tag closes itself. The "space slash bracket" or space/> at the end of the tag signifies a closing tag. 7. Save the file and refresh the page in your browser. The image appears on the page, with a paragraph break between it and the link we made in Exercise 3.

Exercise 5: Formatting Type

If you have printed documents from Microsoft Word or any Adobe program, you have used a markup language. The difference between working in Dreamweaver and printing from Word is that you are aware that you are creating the markup language in the html code. In essence, selecting type and using the "B" button in Word or InDesign to create a bold style is a user interface within the program that informs the printer to markup the selected type. The printer reads the file sent by the program and formats the typography. In Dreamweaver, you will use the interface to add formatting, and you will see the code that is being written for the browser. Thinking of the browser like a printer (and the web as the page) can be helpful for understanding markup language. You will discover that it is not always the perfect simile, as user interaction varies from the printed page to the web browser. The media environment always affects the audience.

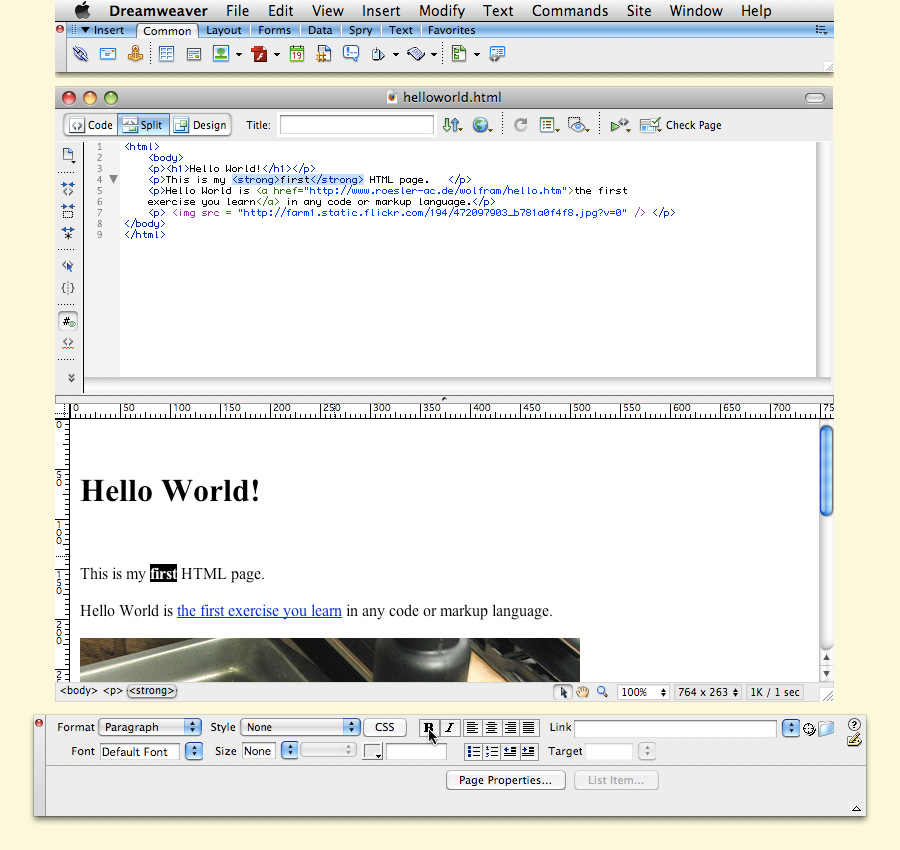

1. The header tag will transform Hello World! into a headline. Insert the tag as demonstrated in this illustration.

2. Formatting type in Dreamweaver is like formatting type in other Adobe programs. Bold and italic styles are one click away, but do notice the code that is added to the html file so that the styles are displayed properly in the browser. Click on Split View. Make the word "first" bold by selecting it and clicking the "B" button in the Properties Palette. Dreamweaver will surround the word with the strong tag.

3. Select the word "any" and click the italicize button in the Properties Palette. Dreamweaver uses the em tag to italicize the word.