Chapter 20 CS4

Download Materials for Chapter 20

The first exercise in this chapter utilizes the final FLA file created in Chapter 19. If you do not have the final FLA file from the Chapter 19 exercises, you can download and use ours: File:Chapter19.fla

Chapter 20: ActionScript3.0

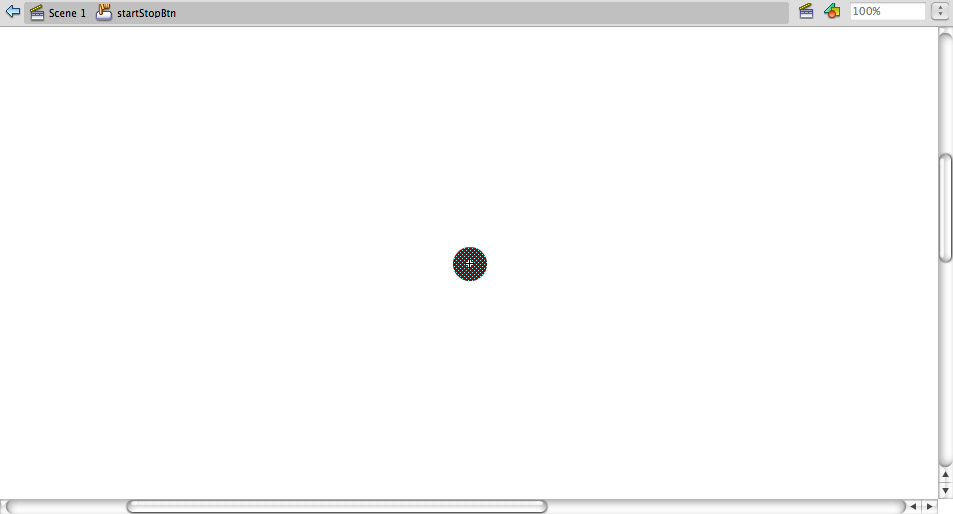

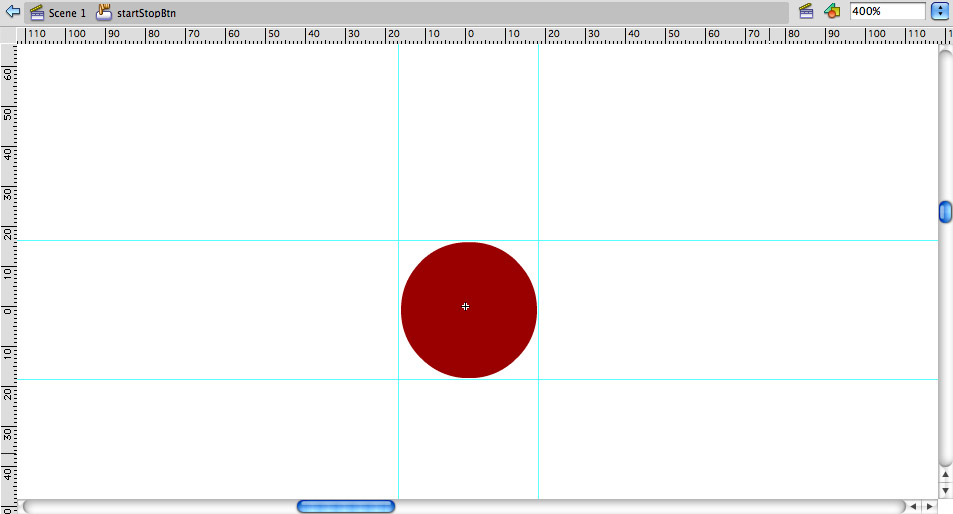

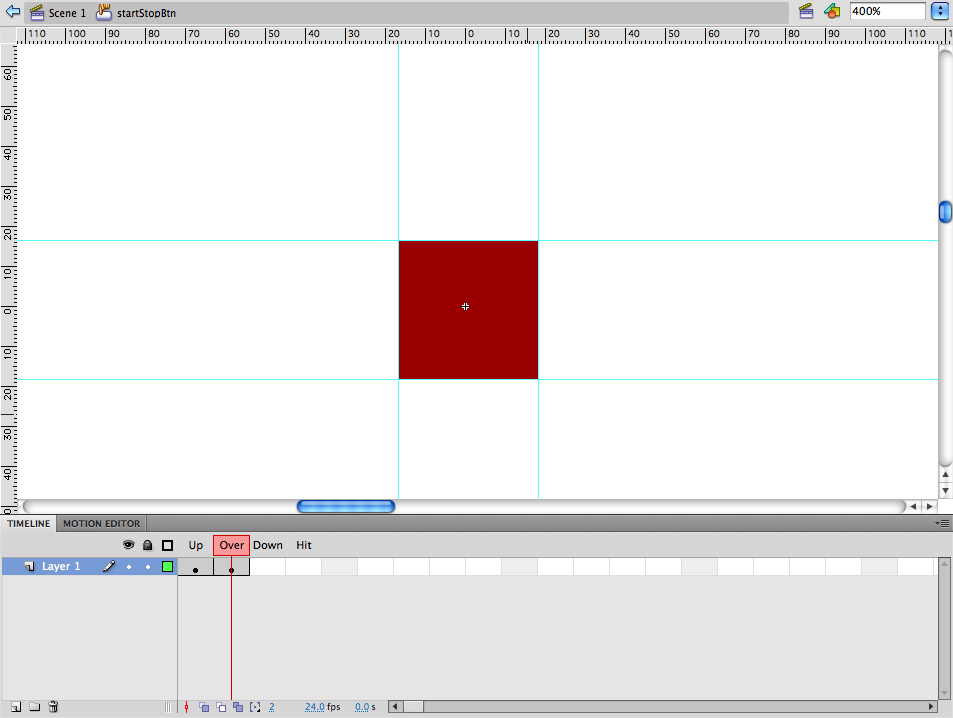

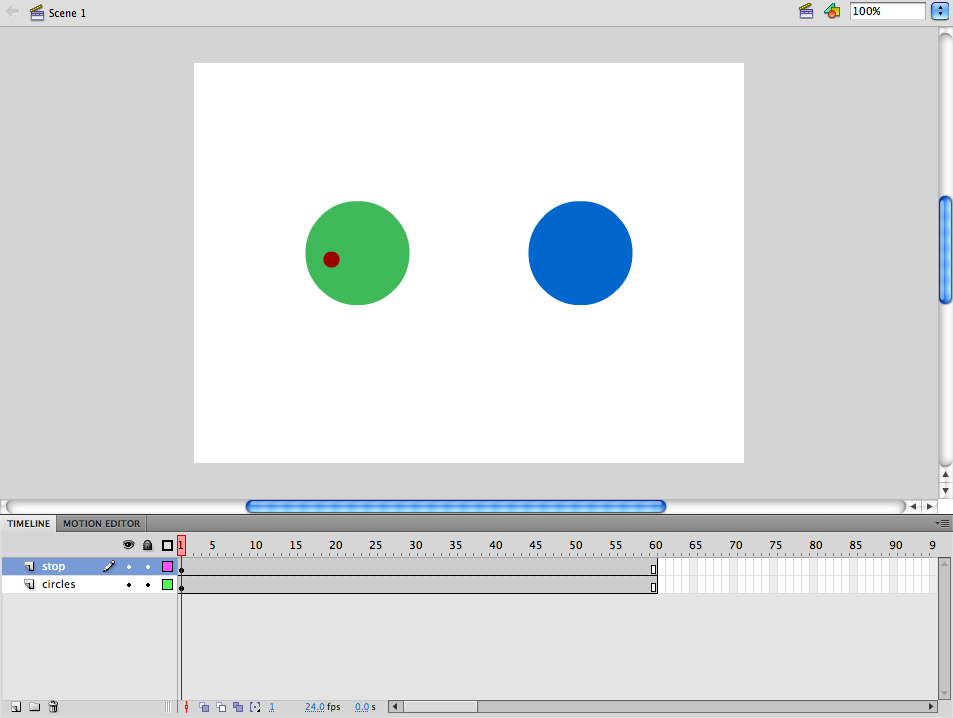

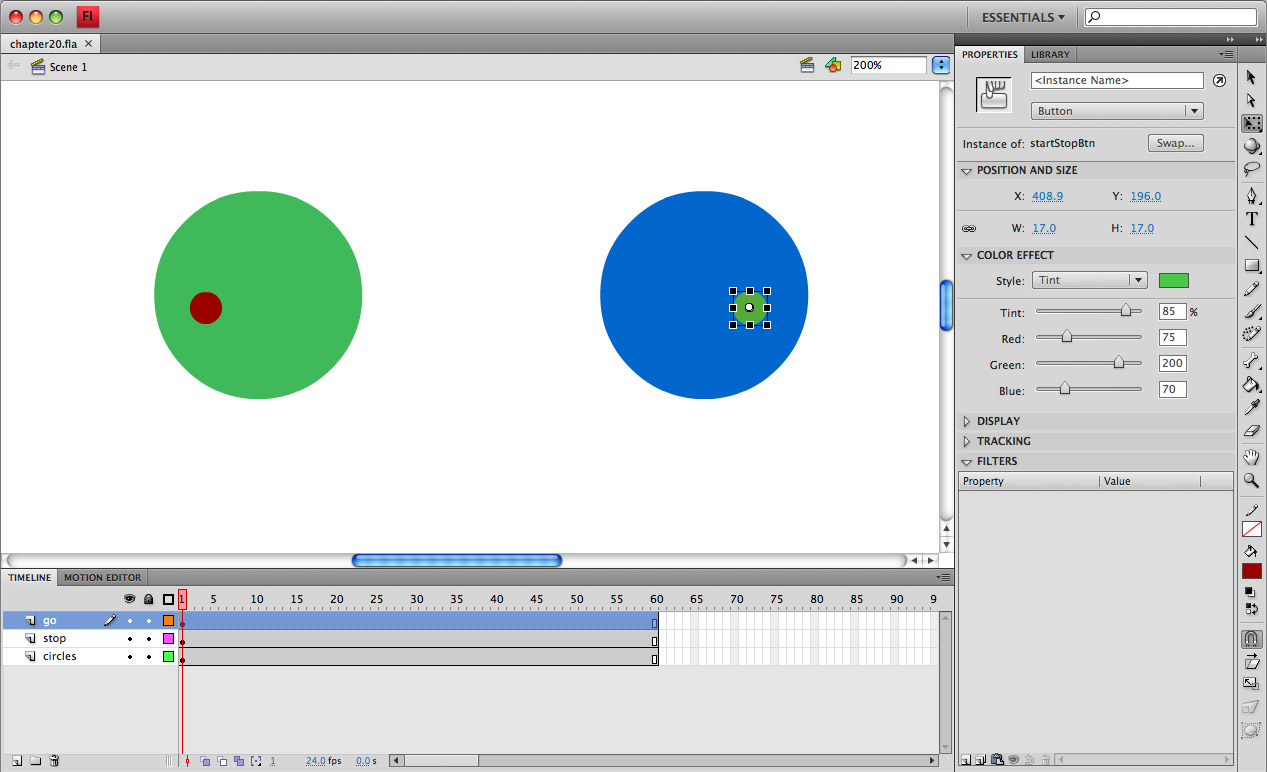

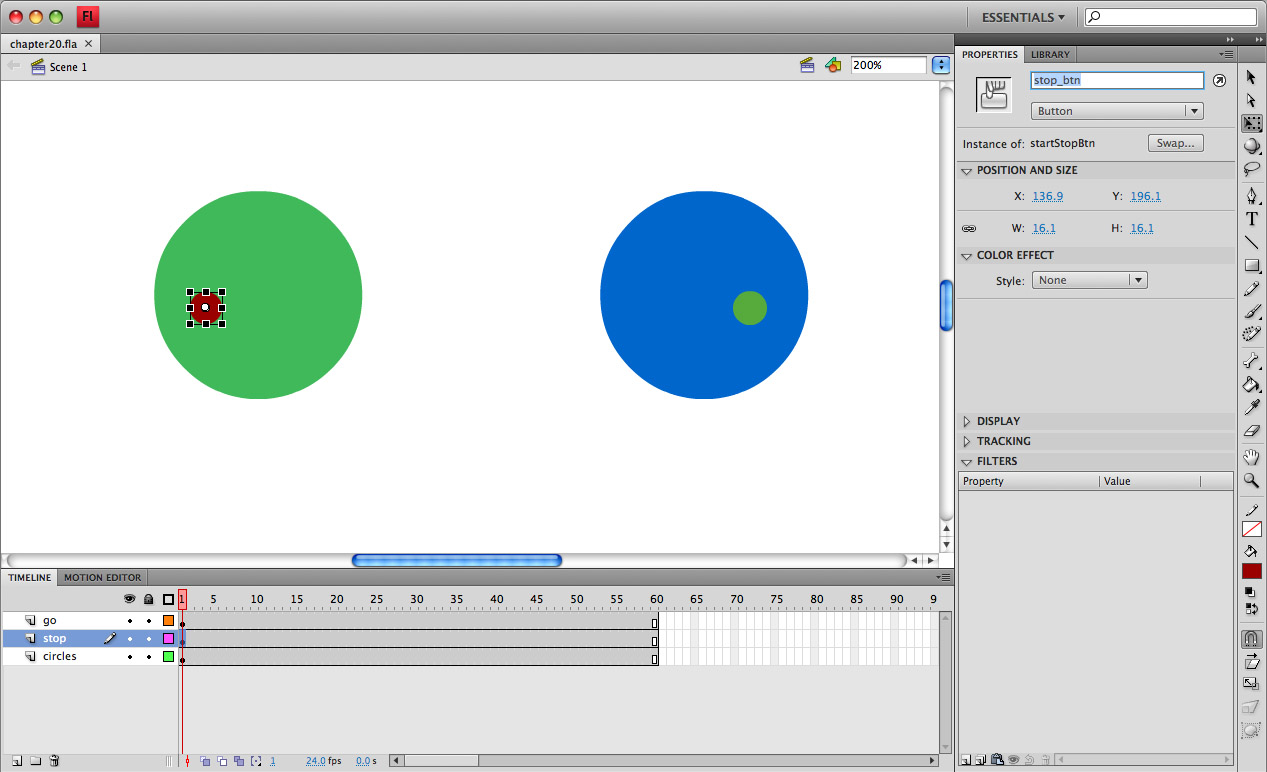

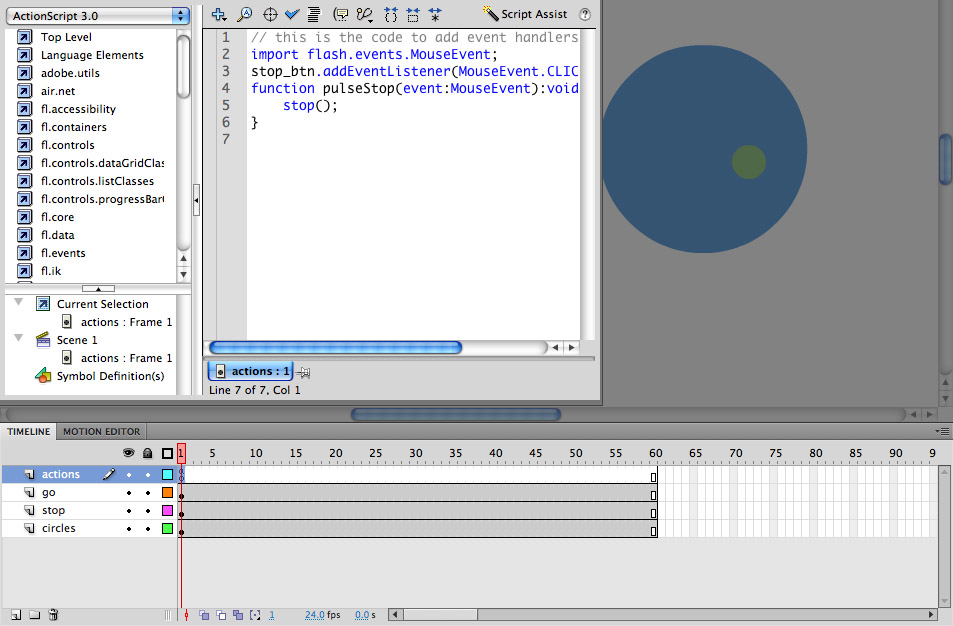

Interactivity is a much ballyhooed concept of the late 20th and early 21st century. We walk around listening to iPods while texting on our cell phones, drive according to directions from a satellite spoken to us live in a calm computerized voice, and are constantly reviewing our blogs, Flickr pages, Google Alerts, and email. Interactivity is not new. The archaeologist Alexander Marschak has argued that the caves at Lascaux was an interactive site; it was a place where people visited to leave reactive marks. From chess to basketball, mahjong to tennis, games are ancient interactive forms of entertainment, intellectual diversion, and fun. Though interactivity is not new, its is increasingly pervasive as a mode of relating to information, people, and entertainment. Building up from the most basic set of logical arguments, early computer programmers created games. Spacewar, Pong, and Space Invaders all share more or less the same basic set of interactivity: Move left; move right; shoot a missle; did it hit?; if it hit, then the alien explodes; if it didn't hit, nothing happens. This basic interactive vocabulary is used in Flash’s programming language, ActionScript3.0. Some of the most basic things we can program are registering the user's clicks to start or stop the Timeline. This is the focus of in the following exercises.

[1] Spacewar, 1961, Martin Graetz, Stephen Russell, and Wayne Wiitanen, computer program for DEC PDP-1 computer. In 1961, at the height of the Cold War US/Soviet space race, three MIT graduate students (Martin Graetz, Stephen Russell, and Wayne Wiitanen) programmed Spacewar, the first video game. In the game two spaceships shoot at each other. The creators added moving stars and changing brightness, a technological feat at the time. If we break the game down into its core interactions, you and your opponent can turn your spaceship right or left, go forward, and shoot. Lastly, the program registers whether your ship has been hit by your opponent’s missile. This is pretty simple, but it forms the basis for much game based interactivity. Put simply: Move your avatar around and shoot things. IMAGE FROM TRIGGER HAPPY Trigger Happy, 1998, Jon Thomson and Alison Craighead, computer program written in Macromedia Director, the predecessor to Flash. ([2]) In 1998 the artist duo Jon Thomson and Alison Craighead created a Space Invaders inspired game and gallery installation called “Trigger Happy”. While the player is playing a game that is very similar to Space Invaders, the content is quite different. The player reads and shoots at snippets of text that create a theoretical argument for the death of individual authoring. The trigger-happy viewer becomes a collaborator in the authoring of the text in the installation. From the players point of view, playing Trigger Happy is like playing Space Invaders where the controller moves the avatar left and right and shoots.